Beyond the spectacle: rethinking immersion in culture

Nicolás Madoery, July 2025

Summary

Culture is being reshaped, not only in what we create, but in how we experience and share it. Immersion is one of the most powerful, and contested, tools in this shift. But to make real sense, we must ask not what these technologies can do, but for whom, with whom, and why.

Situated tools, real stories

Immersive technologies are no longer a speculative horizon. Tools such as augmented reality (AR), spatial sound, virtual environments and interactive systems are already present in cultural spaces, sometimes quietly, sometimes as the core of artistic propositions. Their rise coincides with a growing pressure on the cultural sector to innovate, diversify audiences, and rethink its role in a digitised world.

But beyond the hype, a fundamental question arises: under what conditions can immersive tools genuinely serve cultural processes, and not just tech-driven agendas?

To unlock the potential of immersive technologies, we must stop treating them as universal solutions. Instead, we need to ask: how can these tools serve cultural ecosystems that are not traditionally technological?

Can opera audiences or jazz lovers experience immersion without losing the intimacy of live performance? Can community projects use AR or spatial sound to deepen participation without becoming gimmicky? The answer is yes—if the technology is situated, co-created, and designed with purpose.

Imagine:

- An opera that allows audiences to explore the backstage and process through a pre-performance immersive experience.

- A spatial audio piece that lets jazz audiences walk through the middle of an improvisation.

- A community archive that turns local histories into interactive content.

These are not sci-fi dreams. They’re starting points for grounded, purposeful innovation.

From the museum to the margins

Some sectors are already integrating immersive tech, especially in museums, or new visual art spaces, where real examples abound:

- Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris used AR to augment the experience of Monet’s Water Lilies, providing contextual, visual layers that don’t compete with the original.

- The Dali Museum offers VR journeys into the surreal imagination of the artist.

These cases show how immersive tools can attract new audiences and offer multisensory access to cultural heritage. Large-scale immersive exhibitions dedicated to iconic artists like Picasso, Van Gogh, or Frida Kahlo have also drawn millions of visitors worldwide, blending visual storytelling, music, and projection to reintroduce classic works to contemporary audiences in more accessible, emotional ways.

But in music, the picture is more complex:

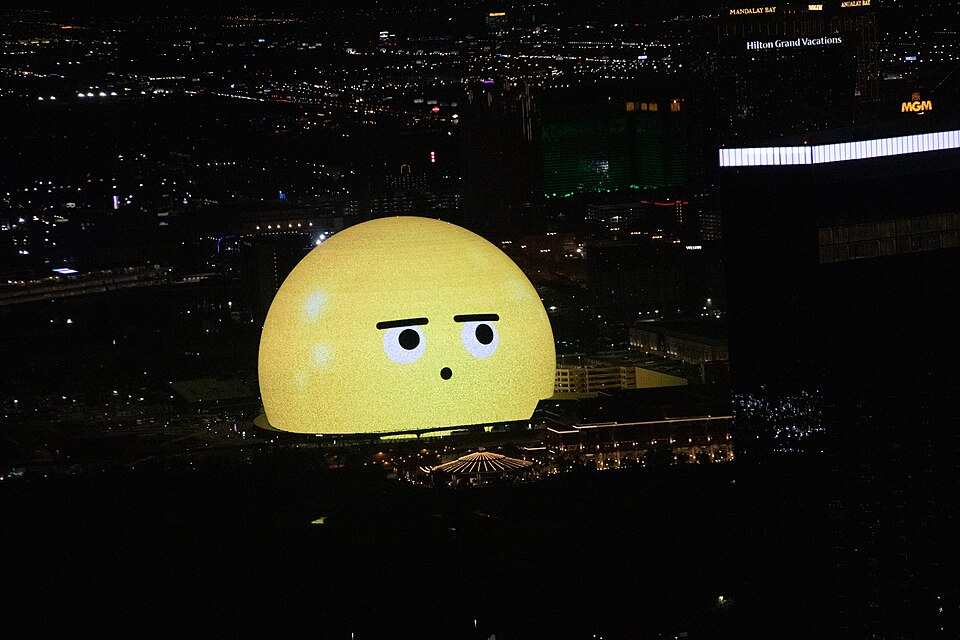

- Beyond big productions like ABBA Voyage or The Sphere in Las Vegas, immersive musical experiences remain limited to niche circuits or experimental scenes.

- Gaming offers powerful models (e.g., Fortnite concerts), but mostly within commercial or mainstream frames.

There is a huge opportunity to translate immersive formats into broader musical contexts—but it demands new thinking, new collaborations, and support structures.

A field of promises and frictions

So, new possibilities are in sight but….

They allow for new sensory formats, hybrid participation, and narrative experimentation. In contexts where physical presence is limited—due to mobility, geography, or social factors—these tools can expand access and emotional connection.

However, these promises operate within a field full of tensions:

- Institutional inertia: many cultural organizations still struggle to integrate immersive tools into their workflows, due to lack of technical capacity, rigid structures, or risk aversion.

- Technological fragmentation: platforms, formats and standards evolve quickly and unevenly, creating confusion and dependency on proprietary tools.

- Economic precarity: immersive projects often rely on short-term funding without long-term plans for maintenance, reuse or integration.

- Access and literacy gaps: while the tools exist, not everyone can use them—due to lack of training, infrastructure or simply time.

What Becomes Possible (If We Design with Care)

While the sector faces real obstacles, immersive technologies also open up new creative and relational possibilities—when approached with care:

- Expanded authorship and co-creation: New tools allow cultural actors to invite communities to shape and share stories together.

- Hybrid access to performances and exhibitions: Virtual stages or spatial sound environments reach audiences excluded by geography or cost.

- New formats for archive activation: Immersive design can turn memory into experience, connecting with audiences emotionally and bodily.

- Post-event engagement and reinterpretation: Immersive formats create ongoing relationships with content, extending cultural presence beyond a single moment.

- Rethinking cultural value: These tools support experiments in participation-based metrics, co-authorship, and non-monetary impact models.

These are not one-size-fits-all solutions. But they are zones of possibility, especially when tools are designed in dialogue with cultural contexts, not simply adapted from commercial ones.

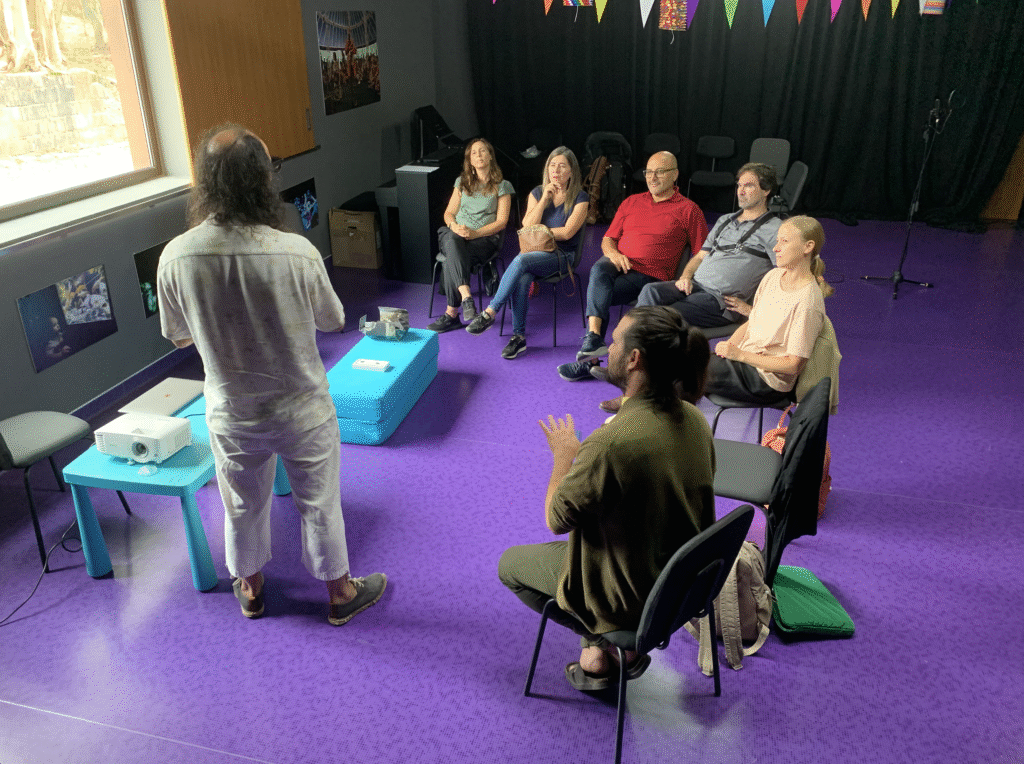

Designing With, not For

Too often, cultural innovation is framed around the creator or institution. But immersive technologies raise a different question: how do audiences experience presence, story, proximity? In many cultural contexts—especially music—the most powerful forms of connection are not mediated by spectacle, but by intimacy and co-presence.

Immersive tools can help rethink the relationship with audiences: not as passive recipients, but as emotional, embodied and interpretive participants. Whether through spatial listening, personalised navigation, or hybrid interaction, immersion can foster new roles for audiences—as co-narrators, co-creators, or co-archivists.

The cost of immersion

For many institutions or collectives, even getting started feels out of reach. Beyond the technical learning curve, there’s an economic reality: immersive projects often require software licenses, hardware, dedicated time, and support teams. Even low-cost prototypes imply a reallocation of resources in already stretched contexts.

Moreover, the return on investment is rarely immediate or financial. While immersive formats may attract new audiences or visibility, they don’t always translate into sustainable models. This tension between exploration and viability is at the heart of many cultural hesitations—and must be named clearly.

What happens after the prototype?

Experimentation is essential—but what happens next? Many immersive initiatives disappear once the funding ends, leaving little behind in terms of learning or legacy. For immersive technologies to take root in the cultural field, we need to plan for their afterlife: documenting processes, enabling reuse, and building communities of practice where tools and experiences can evolve.

This requires not just technical support, but cultural infrastructures: archives, workshops, residencies, shared toolkits, and open standards. Otherwise, we risk repeating isolated experiments that never accumulate into sectoral capacity.

Infrastructures for collective immersion

We don’t need to accelerate the adoption of immersive tools. We need to slow down and ask better questions. Cultural relevance is not measured by novelty, but by resonance, inclusion, and care.

But for those questions to be explored meaningfully, the sector needs shared infrastructures, places where it’s safe to experiment, document, fail, and learn together. That is precisely the ambition of projects like AMPLIFY: to support real-world prototyping across diverse contexts, while making tools, reflections and processes openly available.

Open source technologies, in particular, are key to this vision. They not only lower the cost barrier, but allow institutions, artists and communities to appropriate and adapt tools to their needs. They resist obsolescence, foster collaboration, and help avoid vendor lock-in. In a fragmented field, open infrastructures can become the connective tissue.

Immersion, after all, is not about being surrounded by technology. It’s about feeling connected—to a story, a space, a collective. If immersive tools are to serve the cultural sector, they must be shaped by its values: accessibility, care, creativity, and critical reflection.

The future of immersion is not technological. It’s relational, and collective.