Remote Performance

François Matarasso, July 2025

Going online

One of the ways the Covid-19 pandemic changed us was in making it ordinary to communicate online. During the weeks and months of enforced confinement it became normal to sit at a computer and participate in business meetings, university lectures and school lessons. The cultural sector moved what it could online, including live performances and participatory activities, though there has been a marked reduction since the restrictions on face to face work were lifted. We are not really ready, it seems, to enjoy theatre or concerts online if we can be there in person. But whether the obstacles are human (in the kind of experiences we value) or technical (in the quality of online experiences) is unclear. In reality, it is probably both: as I shall argue, it is a mistake to make a binary choice of something that is fundamentally entangled.

The online experience left many of us with mixed feelings. On the one hand, there is the undeniable benefit of being able to communicate easily with people in remote locations and perhaps with some whom we might not otherwise meet. On the other, video can be alienating and exhausting: a day of online calls is somehow much more tiring than a day of face to face meetings. People also miss the easy social interaction so important to everyday life, whether in an office, college or theatre. Nonetheless, for better or worse, videocalls are here to stay so there is a strong incentive to find ways of making the experience as rewarding and pleasant as possible.

Playing music together online

Where music is concerned, videocalls present a distinct problem—the time-lag (or latency) that afflicts online communication. It’s bad enough when it leads speakers to cut across one another but playing together, in time, is the essence of musical life. Music tuition went online during the pandemic and was particularly affected by this problem: playing along with a tutor or with classmates was difficult if not impossible. Unless we can find solutions—technical and pedagogical—to this problem, musicians will not benefit from the opportunities offered by this new technology.

There are two aspects of the problem. One is the speed and reliability of internet connections, which is always variable but especially unstable in the remote and rural areas where the challenge of distance would make it most beneficial to use videoconferencing in teaching, rehearsing and even performance. There is little that AMPLIFY can do to resolve that situation: it depends mainly on advances in communication technology and investment in the most up-to-date equipment.

AMPLIFY is working to make a difference to the other half of the equation: the software that enables people to work together in current circumstances. A new tool, AMPLIFY PORTABLE, is being designed to support online music teaching and rehearsal, and because it is being developed through an ethical human-centric methodology, it should be well suited to musicians’ actual needs in their current context.

But it is essential not to neglect the human side of the equation. The online space is not the same as the present space and it requires us to develop new ways of behaving and being together. What social conventions are appropriate and what makes us uncomfortable? How does the performer or teacher need to adjust their leadership role to make others feel at home in the online world. How can our attention be maintained when it is limited to sight and sound? In its pilots and experiments, AMPLIFY is as concerned with these human questions—the software that will make the technology work for us.

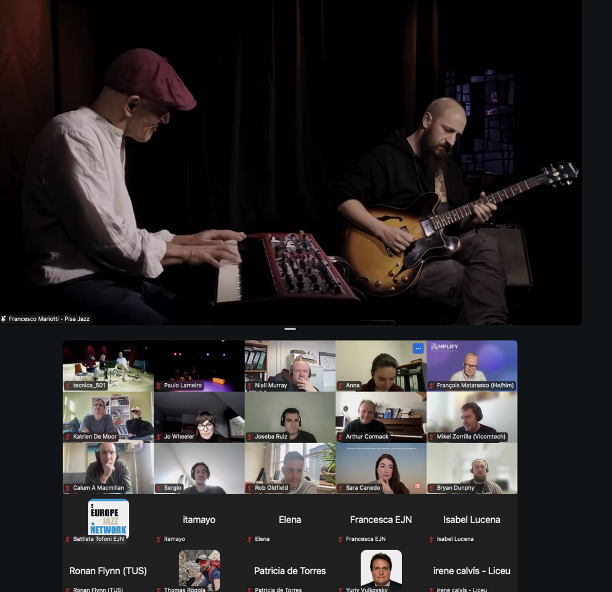

The Remote performance experiment

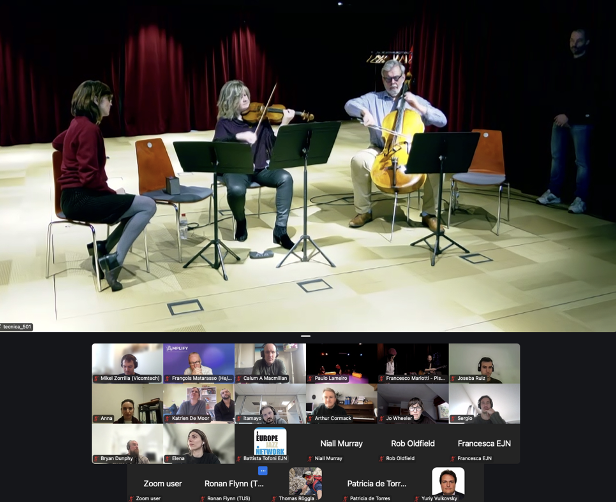

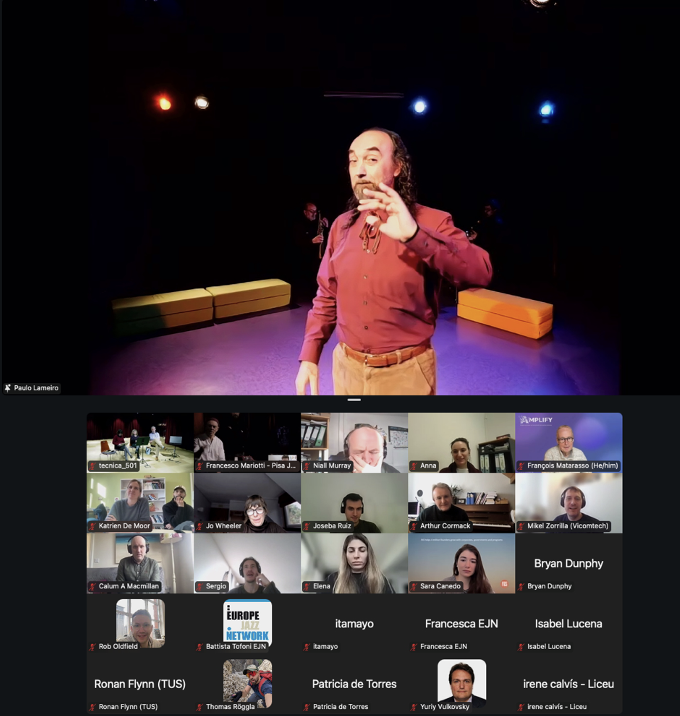

The starting point for this work is to understand the strengths and weaknesses of teaching and performing music online and so, in March 2025, we ran an experiment to gather some initial data. Using the Zoom platform, each of the four pilots participating in AMPLIFY— Fèisean nan Gàidheal, the Liceu Opera House in Barcelona, Cooperativa Paulo Lameiro in Leiria (Portugal) and Toscana Produzione Musica in Pisa—offered a short online musical performance to an audience made up of AMPLIFY members—musicians, technologists and other experts in the field.

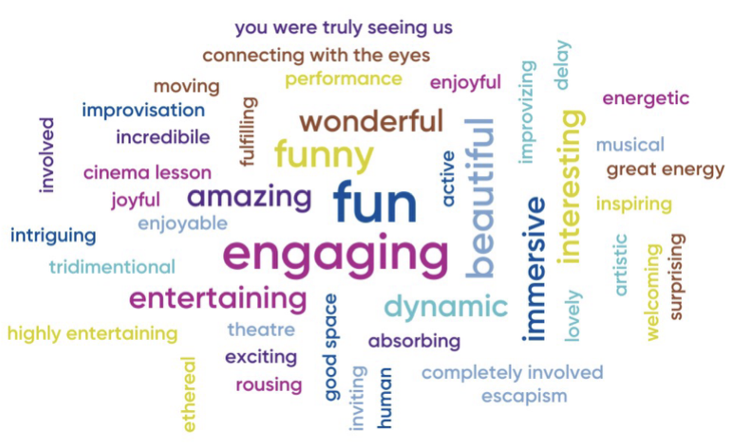

After each of these performances, the audience was invited to comment on the experience directly in conversation and also through the online tool, Mentimeter. Finally, after all the pilots had performed, there was a more detailed questionnaire to complete. All the data was analysed and reported by AMPLIFY’s human-centric and ethical team at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), on whose study this account depends. The quotes below are taken from the questionnaires they designed and analysed.

The first thing we realised was how distinctive was each performance. Perhaps that was to be expected from organisations whose repertoire extended from folk and classical music to jazz, but the differences were much more profound. For example, Fèisean nan Gàidheal focused on intimacy and participation, with the traditional song performances taking place in domestic settings and the camera close in on the musicians. Both singers encouraged the audience to join in the songs, putting the Gaelic language words on screen for the purpose.

“Loved the storytelling and the invitation to sing along – helped with feeling connected and engage with the performers.” (Audience member)

In contrast, the Liceu performance was from a rehearsal studio in the opera house and was characterised by a certain formality often associated with classical music. It was notable too that this was the performance where the audience felt most was lost in the acoustic experience because of the digital platform: several people commented that they wished they could have been there.

“It was a not so immersive experience, despite the skill of the artists and the beauty of the music.” (Audience member)

The other two performances took completely different strategies to reach the audience in their remote locations. Toscana Produzione Musica depended on high quality audio-visual recording, switching between two cameras, one of which offered close up footage of the musicians playing. The result was polished, similar to the kind of live concert one might see on television.

“Having close up video on the performers made a big difference to my engagement – great swapping between cameras was dynamic and absorbing.” (Audience member)

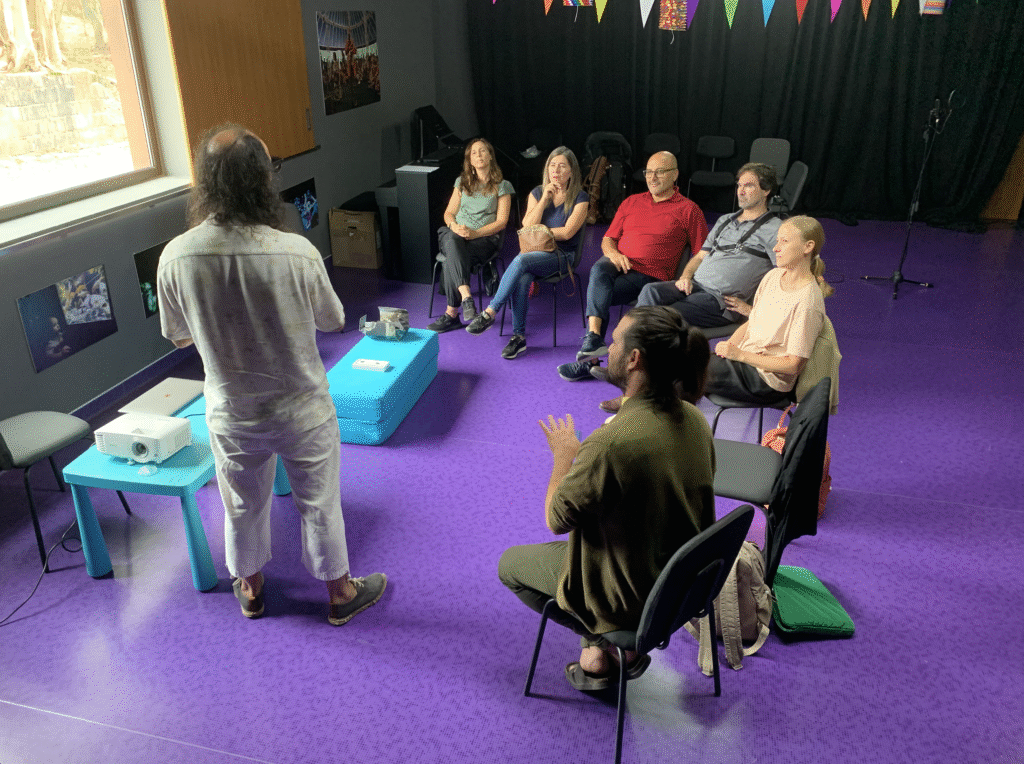

Cooperativa Paulo Lameiro, on the other hand, used only one camera but relied on their incomparable experience of concerts for families with babies to reach across the digital space with a deeply human and committed performance. It was an object lesson in how the skills of the performer can connect with audiences even if they are sitting at their office computer on an ordinary Tuesday morning.

“Very performative – and so engaging, communicating across the digital divide, and making me feel very involved.” (Audience member)

The data produced through the Mentimeter app and the online questionnaire is a rich resource that provides a good understanding of the current state of the art where online music is concerned. Although the audience’s assessments were generally very positive we must take account of its specialist profile, composed as it was of people engaged in AMPLIFY and its issues. As the work progresses, we will involve people from each of the four pilots in experiments that will help us identify both the barriers that people experience and technical and human ways in which they might be overcome.

It is still early days but our aim is to produce a simple software and hardware solution that can make the experience of online teaching and rehearsing a viable supplement to face to face music tuition. Face to face contact will always be the heart of sharing music but as the technology improves it should be possible to supplement this with innovative solutions. The aim isn’t to transfer traditional music formats into digital. AMPLIFY aims to go “beyond streaming” proposing digitally-born novel scenarios that wouldn’t be possible without technology.

Teaching traditional music online

So alongside technical work, we are researching the other aspect of playing together online: the strategies we can use to mitigate or bypass the limitations of hardware and software. Just as a teacher will employ different pedagogical methods for a class of 20 students and for a class of two, video communication asks both artist and audience to behave differently if they are to get the best out of the technology. An online class or an online concert simply cannot be delivered in the same way as a conventional one. The range and effectiveness of these alternative ways of being remain to be discovered.

At the heart of AMPLIFY’s research into online music tuition is Fèisean nan Gàidheal, a cultural organisation that supports young musicians’ learning across Scotland, including the Highlands and Islands. Given the distances involved and the commitment to giving young people access to the best tutors, online teaching has an important potential in their work and during the pandemic it made classes possible. But since then, there has been a return to face to face tuition, despite the practical demands. The challenge now is to develop AMPLIFY PORTABLE as a clear advance on existing software platforms so that online musicmaking can be a good alternative, where cost or other obstacles make face-to-face sessions difficult.

We’re at the beginning of this process, with the first face-t-face sessions with young people and tutors held in Oban and Lewis in recent weeks. The next stage is to clarify users’ requirements of the technology and begin testing some new ideas in September. We’ll post updates in due course, so please check back to see how things are developing.